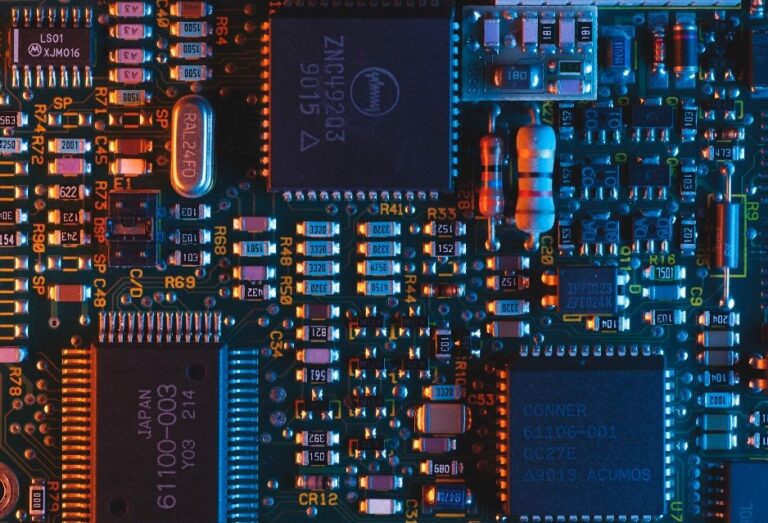

Try to think of a marble and imagine it covered in billions of tiny circuits. Now imagine each of these circuits, known as transistors, endlessly opening and closing at breakneck speed. This is the incredible technological trigger that powers our smartphones, our computers, our cars and even the country’s national security systems. Welcome to the world of chips and semiconductors.

Table of Contents

Chip developments over the years

“All computers, all software, all data storage consists of billions and billions of ones and zeroes generated by these tiny chips,” Professor Chris Miller, a historian at Tufts University, explained on the “Found In Conversation” podcast and author of the award-winning book “Chip War”. “And each of those transistors is smaller than the size of a coronavirus, measured in nanometers.”

The first chip ever had four of these transistors, Miller explains. But on a new iPhone, for example, “the main chip alone will have 15 billion transistors. Four to fifteen billion is the rate of technological progress, and it is a rate that is unmatched in any other sector of the economy.”

Much of this progress is due to the efficiency of global supply chains and cooperation between major companies in different corners of the globe. Yet all this may now be threatened by geopolitical tensions, as governments increasingly seek to develop domestic supplies.

The chip market

It’s no surprise that something this advanced is also extremely complex and expensive to produce. Each step of the process requires very sophisticated tools, and the best ones are often made by only one or two companies globally.

Take lithography, which uses huge machines to beam ultraviolet light onto silicon to cut out the microscopic circuits of transistors. The most advanced lithographic machines weigh over 200 tons and can cost up to $200-250 million. Which creates quite high barriers to entry and over 90% of this market is controlled by the Dutch company ASML.

A similar concentration is seen elsewhere in the chip manufacturing chain. The devices that deposit the thin film on the silicon are produced almost exclusively by the American Applied Materials.

And since these tools and machines must be assembled together in one place for the chips to be produced, this production can only take place in large, expensive foundries that only companies with economies of scale can afford to build and maintain. That’s why chip manufacturing is dominated by a single company: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC).

“Today, there are only three companies that come close to producing cutting-edge processor chips: there is TSMC in the lead, right behind South Korea’s Samsung, and finally Intel in the United States,” says Miller. “And there is no risk of new operators entering this sector.”

He estimates that a single new plant could cost about $20 billion. But with technology moving so fast, it would be able to produce cutting-edge chips for up to three years before being overtaken by a new round of innovations.

Read also: Subcutaneous microchips: how they work, current functionalities and costs

Geopolitical obstacles

Because semiconductors are vital to our daily lives, and because they are used by governments, including in the military, the dominance of some companies and countries in the production process causes problems.

Governments don’t want to be tied to each other for chips, nor do they want to be subject to supply chain problems (like those seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, when chip shortages nearly shut down the auto industry).

“Because of the role of chips in AI, governments focus their efforts on accessing the most advanced chips and blocking access to rivals, partly for commercial reasons, but mostly for military and intelligence reasons,” he says Miller.

For this reason, governments in many of the world’s largest economies have promised funds and incentives to promote domestic chip production.

The European Chips Act aims to mobilize over 43 billion euros of public and private investment in the sector by 2030, while the United States has allocated 52 billion dollars in subsidies for semiconductor production and research and China has made The expansion of domestic production is a fundamental pillar of the “Made in China 2025” strategy.

In many cases, however, the additional investments have been accompanied by more hostile measures. The United States is restricting exports of advanced semiconductors to China and Beijing has launched a security review of US chipmaker Micron Technologies.

Read also: China and Saudi Arabia, the new axis on artificial intelligence