At the recent World Economic Forum annual meeting in Davos, participants made the same mistake they always do: extrapolating from the recent past rather than looking genuinely into the future.

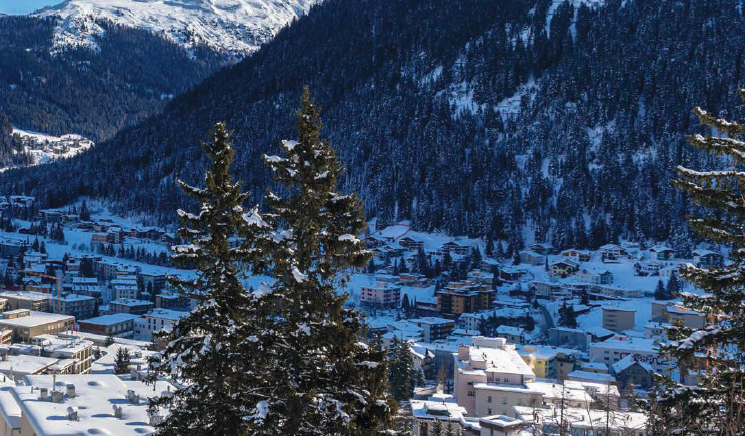

Three key changes would enable the event to ful ll its considerable potential. YORK – I do not attend the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos. But my sense is that, as in previous years, this year’s participants ended up extrapolating more from the recent past than genuinely looking into the future for pivots and tipping points. This was true both at the macro level and in terms of the key individual issues that attracted the most attention, according to multiple media reports (and the media are extremely well represented at this event).

As a result, this globally renowned gathering of infl uential government and corporate leaders appears to have missed, once again, an opportunity fully to realize its considerable potential. There is a reason why Davos tends to be backward-looking. Leaders naturally come to it focused on what they have experienced most recently. If others have experienced the same thing, the Davos echo chamber amplifi es the themes so that they dominate conversations about both recent developments and future prospects. The two meetings before the 2008 global fi nancial crisis had a rather optimistic tone, dismissing the warnings of the few who sensed that the “great moderation” and the era of unfettered fi nance were likely to come to a painful end.

The January 2009 meeting was the complete opposite, projecting crisis and global recession well into the future. Such misreadings of what lies ahead haven’t been limited to periods surrounding crises. Just consider what happened at the previous gathering, in January 2018, and compare it to this year. A year ago, most leaders had just come off the strongest quarter of global growth in years. What’s more, activity was picking up in virtually every country around the world.

As they heard about one another’s experiences, the Davos delegates embraced the notion that the world had entered a period of synchronized growth in which positive feedback loops would turbocharge the process. They gave little attention to the fact that, with the notable exception of the United States, most countries were experiencing largely one-off growth drivers. At this year’s Davos meeting, by contrast, the macro mood is said to have been much gloomier. The consensus was that we are heading for a synchronized slowdown in global growth, with a heightened risk of self-feeding vicious cycles. But again, this fails to distinguish between one-off factors whose impact is temporary and largely reversible – such as the partial US government shutdown and an episode of miscommunication by the Federal reserve – and the sort of secular weakness that Europe is experiencing.

Most of the issue-specific discussions this year focused on China-US trade tensions and Brexit. Here again, the temptation was to extrapolate future developments based excessively on what had just happened. The Davos consensus seemed to be that China-US trade disputes would intensify during 2019. But the likelier scenario is that tensions diminish as China realizes what South Korea, Mexico, and Canada already did in dealing with the US administration: rather than a tit-for-tat tariff escalation, the best approach for a country’s short-term growth and longer-term development is to make concessions to the US on issues of genuine grievance. These include rules that force technology transfers – such as joint-venture requirements – and the theft of intellectual property. On Brexit, the central scenarios at Davos focused on either a continuation of the current no-peace-no-war process or, alternatively, a hard exit for the United Kingdom from the European Union. Yet, because this has already proved to be a very “slow Brexit” process, with Britain’s Parliament repeatedly unable to agree on a replacement for the current EUUK relationship, the probability of a soft Brexit is materially increasing. So is the probability, albeit lower, of a second referendum, which was once thought an unlikely, if not unthinkable outcome. Simply extrapolating the future from what has just occurred usually leads Davos delegates down false trails. Davos – both its organizers and its participants – would do a much better job by making three changes to the way the event is managed. First, the meeting should actively propose alternative scenarios for serious discussion.

This year’s agenda, for example, should have included a possible return in 2019 to divergent growth and the associated risks and opportunities. In addition, Davos should collect and discuss best practices for dealing with usual levels of uncertainty for both businesses and government policymaking. Finally, when it comes to short-term prospects, the event needs to spend a lot more time on other themes that I suspect will prove more important than either Brexit or China-US trade tensions in the period ahead. These include the changing attitude toward regionalism, central-bank policy challenges, and the scope for more government-policy coordination among advanced economies. The annual Davos gathering is too big an opportunity not to be exploited properly.

Yet year after year the focus has ended up more backward-looking than forwardlooking, and the just-concluded iteration appears to have been no exception. A revamp would play an important role in fulfi lling the stated objective of Davos: engaging “the foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas.” And it would ensure that more of the participants go looking for actionable, substantive content rather than ending up being there primarily to see and be seen N