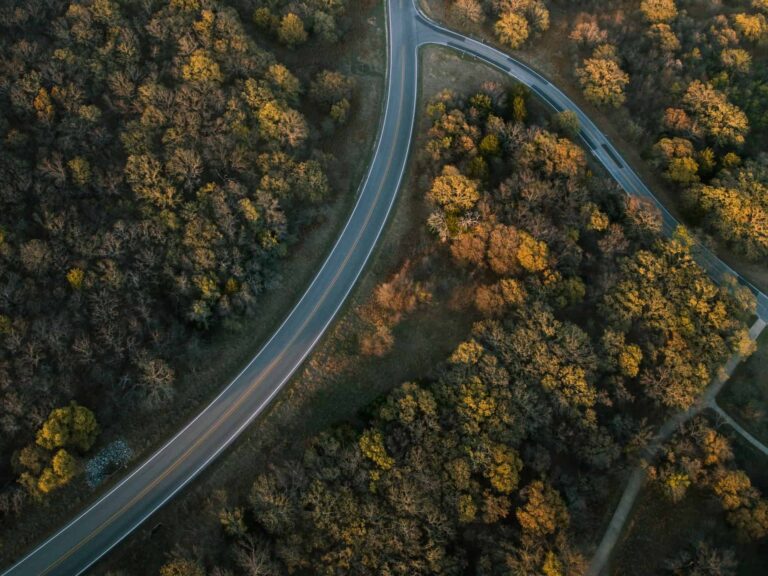

The goal is ambitious: to build 3,000 kilometers of roads in Sweden by 2045 that can recharge electric cars simply as they pass.

But the will to get serious is there. So much so that, while Europe wrangles over the law that should oblige member states to put only “zero-carb” cars on sale by 2035, the Scandinavian country is studying the total electrification of the E20 highway.

The road connects the logistics hubs of Hallsberg and Örebro, in the center between the country’s three major cities, Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö.

Table of Contents

The difficulties and the challenge of the Swedish electric highway

The E20 is thus expected to become the mother of all Swedish roads with “automatic” charging. But the series of “buts” is long.

First of all, it is clear that the use of charging systems embedded in the asphalt of this highway requires the use of vehicles that themselves need to be experimented with. And the costs can be not insignificant.

As for E20, where the project is still in the procurement phase, work is estimated to be finished by 2025. And we are in Sweden, where besides Scandinavian efficiency, pilot projects in sustainable mobility are uncountable. And so, consequently, is the knowledge.

How does the electric highway work?

But how does (or how could) the electrically charged E20 work? Let’s start with the assumption, as mentioned above, that the work is in the procurement phase. Estimated to be finished by 2025.

But that the technology with which to make recharging automatic for the vehicles traveling on the road has yet to be identified. In this regard, there are between alternatives: catenary system, inductive system and conductive system:

- the catenary system can only be used for heavy vehicles. It uses overhead wires to supply electricity to a special type of bus or streetcar. It would basically turn trucks traveling that stretch of road into trolleybuses;

- conductive charging works the same way as in a smartphone. Instead of connecting to a charger, special electric vehicles skim the road at a pad or plate that, when the vehicle is on top, charges the vehicle without the need for wires;

- the inductive charging system uses special equipment buried under the road that sends electricity to an electric vehicle coil which then provides power to the batteries.

Read also: European zero-emission road freight transport: a feasible goal by 2050

The HGV challenge

The Swedish trial is prioritizing finding a solution to optimize heavy vehicle traffic. So much so that a wireless electric road for trucks and buses was built as early as 2020 in the island city of Visby.

But the main challenge is to find a technology that allows trucks to run at full load. This is something that overweight batteries could make difficult. But a study commissioned Swedish Transport Administration does not rule out a benefit for private car movement as well.

By simulating the movements of 412 private cars on the Swedish road network, it was found that by combining studies on domestic decarbonization with those on decarbonization it would be possible to reduce battery size by up to 70 percent.

In addition, it was determined that only 25 percent of all Swedish roads would be suitable for efficiency with an of the Electric Road System (ERS). As in: for many, but not for all.

The other experiments

Other countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and India are increasing the construction of ERS systems.

Sweden has partnered with Germany and France to exchange experiences through authorities and research collaborations on electric roads.

Germany and Sweden have had demonstration facilities on public roads for several years. While France plans to purchase a pilot section with an electric road.

Read also: Solar roads: pros and cons of the first experimentations of photovoltaic panels instead of asphalt